On Choosy Coffee Chats

There are all kinds of articles out there giving advice on how to ask someone you professionally admire out for a coffee chat (because we all know how important networking is in getting a job and moving up The ladder). But what about the kind-hearted yet unbelievably busy invitee? Let’s acknowledge that we can’t help everyone. Today we explore how to choose who to help, and how to say no (when appropriate).

Target Audience: Working professionals, new grads, executives

Most people in past generations were raised to believe that if you work hard to become a skilled and capable person, you will get a good job and have a good career. Nowadays, being good isn’t good enough. The myth of meritocracy leads to a big gap in reality: it’s not just what you know but who you know.

Networking is a crucial prerequisite to the job hunt for most knowledge-workers (and other professions!). A somewhat outdated (2015) LinkedIn study shows the industries that hire the most from their networks:

My personal take on relying on the network as a hiring pool for knowledge workers is as follows: in knowledge work, it is very difficult to judge the quality of the candidate until you’ve worked with them for a while. This is known as asymmetric information – the candidate knows their skills but the potential employer can’t be sure (like they would be with, let’s say, an artist, where they could evaluate their work immediately). So the network functions as a credible signal that the candidate is actually good – they have the endorsement of trusted others. To explore this topic more, check out the classic paper on the subject by Michael Spence (1973).

So the point is that we all know that networking matters, especially for those “at the beginning” of their careers and those who are desperate for a job. The newbies? - we’re talking interns, analysts, and undergrads - are told over and over that they have to be persistent in asking for coffee chats. Hence the explosion of literature and blogs on how to ‘master the coffee chat’, or how to make sure your email doesn’t get ignored.

But what about the people being asked for coffee chats?

Assuming we are talking about nice people who generally want to help, but who also have a day job to get on with, how does one decide who to help and who to ignore?

I work in an industry where coffee chats are the standard. In consulting, the expectations to network internally in the firm are very high to become staffed on a project or to gather important information. Pre-COVID, I would have at least one internal coffee chat a day. But I would also be getting external coffee chat requests as well from people looking to “learn about my journey”, aka get help on their job hunt. And while so far I am pretty darn successful at saying yes to everyone, I am nothing short of overwhelmed.

Coffee chats can be overwhelming!

It turns out, I’m not the only one. Chatting with some of my colleagues from a bunch of different companies, coffee chat requests have become increasingly aggressive. (Why? Probably due to a combination of a) it’s becoming more well-known that networking is needed, b) more educated people looking to get into knowledge-work jobs, and c) more supply of qualified workers in the workplace compared to available positions). The requests range from a friend or colleague making an introduction to a random person guessing the unique make-up of your corporate email address. I get earnest requests from lovely people, and then I get requests from people who see only the name of my employer and don’t care at all who I am but pretend to so that they can get a job (spoiler: I always try to help but in reality there is a whole Talent group for that function and I don’t work in Talent).

I imaginary laughed at this

The Cost of Coffee Chats

As I see it, there are two main costs to coffee chats. The first is your time – this is time you could have otherwise spent on revenue-generating things. And the second is your cognitive energy – where your thinking and emotion are devoted to this interaction. Especially if you are an introvert. Especially if your days are already 8 hours on Zoom. Once you hand over so much of your day to others, there’s not a lot left for you.

And… THERE’S ONLY SO MUCH COFFEE ONE CAN DRINK!!

But… you’re a vampire?

How to Decide Who To Help

To better understand who we should help, let’s look at who we do help as suggested by Behavioural Science.

Homophily.

This is a fancy word to describe how people tend to gravitate towards other people who are like themselves. People who are like us – in look and in thought – don’t challenge our world views, and that makes us feel comfortable. Many times people don’t even know they’re doing it. But the problem with homophily is that it leads to convergence of ideas (i.e., maybe the team doesn’t spot a glaring mistake) and less access to mentorship for anyone who is different. So behavioural science would suggest that people fall prey to the lure of homophily and tend to accept coffee chat requests from people in whom they see something of themselves, like maybe they went to a similar university or live in a similar neighbourhood.

Reciprocity.

Reciprocity is a social norm that suggests we prefer responding to others’ actions with an equivalent action. Like how if someone gives you a birthday gift, you feel obligated to give them a gift back on their birthday. When a friend or colleague asks us to have a coffee chat with their neighbour’s child who has a mild interest in engineering, we say yes. We say yes because it’s a sign of friendship (in that we are signalling we value that relationship) but also because reciprocity ties our decision to their future behaviour. Say yes, and they’ll maybe say yes to a similar request down the road. Say no, and they’ll say no to a similar request down the road. So if a friend or colleague asks for you to have a coffee chat with someone, you’re probably going to say yes.

Wow, networking over WINE, these chickens know how to party

Now, How Should We Decide Who and How To Help?

Adam Grant, Professor at Wharton, has a fantastic take on who to help. In his book, Give and Take, he divides behaviours into taking, giving, or exchanging. But he notices that people tend towards one of those three. Hhe divides the world into givers and takers (and matchers – the in-betweeners). Takers put themselves first, seeing being competitive as the only true way to survive or get ahead. Givers put the needs of others ahead of their own, and prioritize helping others. Givers put themselves at risk by helping others, but are also more likely to enjoy more career success, and perhaps even positive emotions.

So, with that in mind, who should we help? Probably the people who are givers and matchers. They are likely to help you back, pay the advice or connection forward, or are motivated to make a positive impact beyond their own gain.

The trap? You can’t always tell who is a giver and who is a taker right away. And don’t conflate politeness for generosity. There are takers who are very polite (maybe even charming!) but are still self-interested, and givers who are rough around the edges. Want to see which kind you are? Take Adam Grant’s self-assessment. How do these people treat peers and subordinates? Are they willing to help others or do they just want to climb the ladder?

Most of the time you are being approached by strangers so use your spidey senses to assess the nature of the person asking you for a coffee chat. If you have limited time for coffee chats, prioritize the requests from those who are going to maximize the good of your time and advice.

Here is a list of questions that will help you decided whether or not to accept that coffee chat:

Should I accept this coffee chat request?

I have often been given the advice that I need to learn how to say ‘no’. But I empathize with the job seeker, and I love, love, love helping! And I’m sure you do too. So how do we protect ourselves and our hearts in all of this?

So, How To Say No?

… without sounding like a jerk. I found another blog post with some great suggestions.

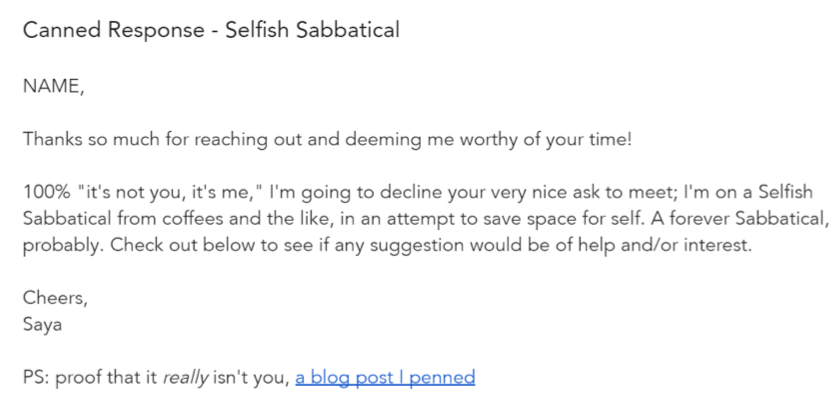

1. The canned response. At the end, they include alternative suggestions. Here is their example:

2. He also suggests a FAQ page on his site (which obviously only works in some cases) to the question of “can I pick your brain?” This is a great idea to separate out those who want to chat with you for information vs those who want to chat with you because they see you as someone who will directly help in getting them a job.

3. If you think someone else could help, make the introduction. But make sure to ask them first!

4. Pass them along to some other resources that could help. Maybe there is a LinkedIn community or a recruiting group for your company.

In summary, the suggested approach to a request you can’t meet is to kindly and gently acknowledge the request, give a good reason for saying no (because we want to minimize the feeling of rejection!), and giving a viable and thoughtful alternative. You might even be helping MORE.

I have gained a lot from the coffee chats I’ve had with people I professionally admire, friends, peers, and juniors over the years. I have been helped along with some great advice and kindness – and I am grateful. My goal is to repay these kind folks through my success, expressing to them their specific impact on me and be as helpful as possible to others. I also happen to find having coffee chats and being able to be helpful to be very rewarding. So I’m going to try this new approach. Wish me luck!

If you are a coffee chat requestor, here is a great article to help you with your coffee chat requests.

With love and coffee jitters,